Groundwork for a Treatise on the Semiotics of Shit-facedness

/ language / Drew

NOTE: This is a work in progress. Nobody should be reading this. It’s not good, not ready for prime time, and is probably full of all sorts of incoherent nonsense and misinformation. Probably typos too.

Before we get to the topic of this little essay, a disclaimer. A lengthy, discursive disclaimer, written in the second person, composed of sentences with entirely too many clauses.

If you’ve ever tried to master a foreign language in adulthood, and you’re neurotically self aware and self critical, you’ve almost certainly spent some time frustrated the crudity of the language you can command even at your sharpest, at least when compared to your ability to use the sounds and syntax of your native language to express yourself. You’ve probably spent entirely too much time lamenting the unavoidable conclusion that conscious study, no matter how intense and sustained, will never produce the same results as the unconscious, mysterious forces that turned you into a fluent speaker of English (or whatever happens to be your first language). There’s no substitute for living in a language as a young person. There are associations that come with every word, phrase and idiom, shades of literal meaning and connotation, whose significance will elude even the most conscientious student of a second language. It’s one of those inescapable facts of life: death, taxes and the inelasticity of the adult brain.

That shouldn’t stop you, or anyone of else from plumbing the depths of another language. And it certainly doesn’t stop me from analyzing the Polish language from all sides. Which brings us to the disclaimer. Please keep this sorry state of affairs in mind as you read this little essay. Although I’ve done my best to to substantiate the claims below, and at least one native speaker seems to think that I’m not saying anything completely ridiculous, I am a highly fallible, non-native, Polish speaker who still struggles to construct complete, intelligible sentences in Polish. Moreover, I have almost certainly add some dubious assertions. To wit, you’ll find smarter more authoritative sources than myself. In that spirit I’ll offer a couple recommendations as part of my oh so humble disclaimer:

-

If you’d like to get a sense of all of the subtleties of language, I suggest you read someone like Umberto Eco, or Douglas Hofstaedter who have both written about the art of translation. There’s no better way to understand “connotation” in its most general sense than studying how translators do their jobs.

-

If you’re hoping to sharpen up your Polish language skills, you should find a qualified Polish language teacher, and plan to spend lots of time immersed in the language.

-

If you really care about the topic of this essay, which is to say, the myriad ways to say “drunk” in Polish, I recommend first-hand learning. In a pub, beer or with Polish friends at home.

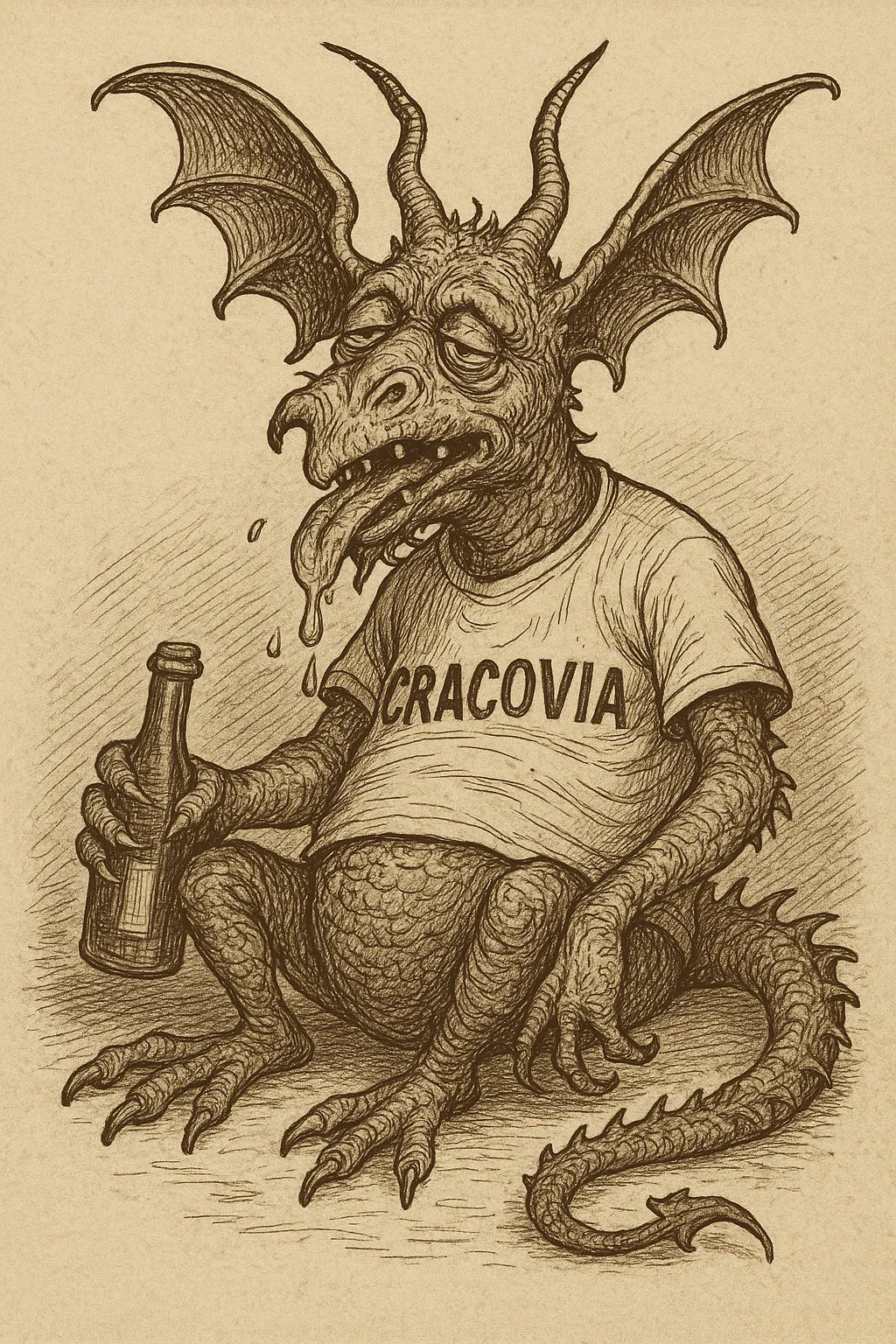

So let’s get started. If you’d like stumble down the rabbit hole with a linguistically curious rabbit who still freezes when faced with the cruel, slav-ering (pun most definitely intended) visage of a seemingly impenetrable, un-declinable and possibly unpronounceable Jabberwocky of a Polish word, keep reading.

The infinite variety of ways to say inebriated in English and Polish

There’s evidence that humans have been drinking alcoholic beverages of one kind or the other for thousands of years. It’s certainly no surprise given its significance in human culture, that you’ll find a rich set of words and expressions for describing a state of inebriation. In English, we might describe someone in everyday life as “tipsy” if we want a commonly understood, nonjudgmental term for someone who’s feeling the effect of alcohol but who is far from mortally impaired. At the opposite end of the spectrum, if we describe someone as “shit-faced”, the moral opprobrium is clear. The scatological “shit” (more on vulgarity, cursing and their role here later) intensifies the meaning and reinforces the judgment. We back off a little by being more descriptive and less explicitly judgmental, describing someone as “falling down” drunk. We can be a bit whimsical—and indirect or euphemistic—by employing the now somewhat archaic “three sheets to the wind”. Finally, if we want to be legalistic or technical we might use a term like “inebriated”, “impaired”, “intoxicated”, or, of course, the phrase “under the influence”. The context, our intent, moral valence, and the more measurable, “objective” notion of the degree of inebriation all inform the words we choose to express our assessment and attitude. All of this language orbits the prototypical “drunk” in the web of alcohol-related language in an English speaker’s mind.

In Polish, the stalwart, work-a-day equivalent of the word “drunk” is “pijany”. Its literal meaning and etymology is very close to drunk. The verb to drink in Polish is “pić”. It is the adjective form of that verb—the masculine form found in a dictionary—comes from a basic, general term for consuming liquids. (As a related aside, I’ll note that Poland’s quintessential distilled liquor, vodka, or “wódka” literally means “little water”. Not surprising for the essential beverage, especially considering the even more celebratory French construction “l’eau de vie” and their Northern European cousin, aquavit, which both trace back to Latin “Aqua vitae”.) The word “pijany” occupies the same place as as “drunk” in the Polish speaker’s mind. It sits somewhere near the center of an equally rich semantic web of descriptive words for drunkenness. The elderly friend who feels a happy buzz after a drinking a tipple of his favorite black currant nalewka, might report being “wstawiony”, an adjective form descended from a rather generic, neutral verb “wstawić” (to “put into place”). Despite not having the descriptive quality of “tipsy”, a Polish speaker will tell you that its usage is the same, and in that sense the meaning is the same even though the words share no literal meaning. In terms of intensity, judgment and vulgarity, most Poles will likely tell you that the near equivalent of “shit-faced” is probably “napierdolony”, an adjective form of a vulgar verb that means “to fuck” in its literal and figurative vulgar senses (I’m not entirely sure how rude “pissed” is in British English, but I think that this translation does not entirely work). I suppose “fucked up” might also be a fine translation, though in (American) English, this phrase (to me) feels more appropriate for describing the effect of drugs. I’ll also note (this is highly subjective) that it shares more aesthetically with “shit faced” than “fucked up”. Polish also has many euphemisms, including its own older expressions like “na rauszu” (which comes directly from te German word Rausch for drunk or tipsy which is related to “rush” in English which is itself interesting), which also happens to be the title of that fine Mads Mikkelsen film “Druk”, translated into English as “Another Round”. I’ll pull that particular thread later since it touches on the language used in different parts of the world and how that may or may not relate to how drinking habits and the culture around drinking varies across Europe (it’s this sort of content you should be taking with a grain of salt; c.f., my earlier disclaimer). Finally, like English, in the legal system you’re going to see “nietrzeźwy” is something very close to “not sober”, formal, neutral even medical/scientific.

More to come…

Notes

I have several ideas for how to approach fleshing this out:

- Find a way to cite examples from the web and/or from books

- See if I can keep the tone light and comic, less staid than my other blog entry

- Build a graphic that shows level of formality of different words

- Find a Polish embedding model, do a 2D dimension reduction like t-SNE, and show the words and expressions

- Create an accompanying video

- Create a language “cheat sheet”, possibly based on the notes below.

- Collocations (sp?) involving drunk like “stinking drunk” in English

- Letting out the peacock (“puścic pawia” (sp?))

- Find that article about ambivalence toward pigs, that weird Arabic-Polish paper

- Cite that Wet versus Dry communities paper.

- Look at the Mads Mikkelson move title translations, maybe as part of the wet-dry distinction you see in the academic literature.

Themes:

- Nature and “level” of vulgarity. Possibly reference McWhorter’s “dirty words” book or others of that ilk (forget, but didn’t I read another one?)

- Nature and “level” of formality, setting and context.

- Nature and “level” of drunkenness

- What we mean by lighthearted, serious, comic, formal, etc.

- What we mean by “euphemistic”

- Context matters and is super hard to judge if you’re an outsider!

Polish Expressions for Being Drunk

A structured list of Polish words and phrases describing states of drunkenness, from the most polite/euphemistic to the most vulgar.

Neutral / Formal

- nietrzeźwy – neutral, official, used in documents.

- w stanie nietrzeźwości – formal, medical/legal phrase.

- po spożyciu alkoholu – very official, euphemistic.

- pod wpływem – neutral, commonly used.

Polite / Euphemistic / Humorous

- wstawiony – slightly drunk, common and polite.

- podchmielony – gentle, suggests a beer or two.

- na rauszu – slightly old-fashioned, elegant euphemism.

- po kieliszku / po drinku – soft, suggests moderation.

- zrobiony wesoły – half-joking, implies a merry state.

- ma w czubie – idiom, lighthearted, “a bit under the influence.”

- dobrze podlany – vivid but not offensive, moderately drunk.

Everyday / Stronger

- pijany – the basic, neutral word.

- zalany – very colloquial, “soaked in alcohol.”

- nawalony – strong, colloquial.

- urżnięty – colloquial, heavily drunk.

- narypany – slangy, less polite.

- zrobiony w trupa – slang, “drunk to the point of collapse.”

Vulgar / Harsh

- naj*bany – very colloquial and vulgar, extremely drunk.

- uchlany – vulgar but common.

- nap*rdolony – very strong, vulgar, “shit-faced.”

- naj*bany w trzy dupy – extremely vulgar, exaggerated form.